On Wednesday, January 28, the two Cypriot leaders, Nicos Christodoulides and Tufan Erhürman, failed to agree on opening new crossing points along the Green Line to build trust and improve the daily lives of their citizens. This was the UN’s hope for reversing the negative climate on the island and supporting a renewed peace effort after almost nine years of complete deadlock. So far, this modest hope has been dashed.

The consequences of the deadlock could prove much more adverse for Cyprus if Cypriot leaders do not change their approach to finding consensus. The preparatory step of holding informal expanded “5+1” meetings under the auspices of the UN, to which all three Guarantor Powers (Greece, Turkey, UK) are invited, with the aim of kick-starting full-scale negotiations, has been postponed. Thus, the whole effort to resume the process has stalled and may have already been doomed before it even begins. The citizens on both sides of the Green Line that cuts through the island, experiencing the anachronistic conditions of a de facto division for decades, are paying the highest price.

In a resolution passed just two days after the failure, the Security Council warned once again that “the status quo is unsustainable, that the situation on the ground is not static, and that the lack of an agreement furthers political tensions and deepens the estrangement of both communities, risking irreversible changes on the ground, and reducing the prospects of a settlement.”

Cracks in the division

The crossing points are cracks in the division. They constitute the only practical opportunity that has been given to ordinary people over the last two decades to communicate and interact on the divided island. However, citizens often have to wait in long queues on a daily basis in order to be able to cross. This is a vivid illustration of what happens when citizens are condemned to live in the past and suffer the consequences of the disagreements of their leaders. Since the 1980s, either one leader or the other, and sometimes both, have rejected at least six comprehensive proposals for a reunification agreement in the form of a “bi-zonal, bi-communal federation with political equality,” as agreed in theory since the 1970s and recorded in dozens of Security Council resolutions. The division continues and deepens despite the fact that Cyprus has been a member state of the European Union since 2004.

At this juncture, the two leaders disagree on how to restart full-scale negotiations from where they were left off “at Crans Montana,” when a “historic opportunity” to reach a strategic agreement was lost almost nine years ago. However, Secretary-General António Guterres agreed to offer his good offices, assessing at the same time the sincere will of each leader to actually move forward. So he called on them to open new crossing points to prove it. Christodoulides and the then-Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar had agreed on four crossing points last March, but failed to implement their agreement because they disagreed on which ones to open.

The failure of Christodoulides and Erhürman to agree on the issue is naturally raising questions:

What is preventing the two leaders from opening crossing points?

If they cannot manage to do this, how can they resolve more complex issues and reach a settlement in Cyprus?

Departing from the joint meeting between Christodoulides and Erhürman, the Secretary-General’s personal envoy, Maria Angela Holguin, stated that the informal meeting “5+1” “is not going to be (held) for the moment”. In an interview with the newspaper “Politis” shortly after, Holguin criticized the lack of concrete steps in the field of confidence building measures, stressing that “small, consistent steps that demonstrate reliability and mutual benefit can gradually rebuild confidence.” “Trust is not created by declarations alone — it is built through sustained and daily actions” she explained.

Consequences

In the wake of the failure, the Security Council decided to renew for another year the mandate of the UN peacekeeping force UNFICYP, which has been on the island since 1964, but asked the Secretary-General to submit reports in July 2026 and January 2027 “in particular on progress towards reaching a consensus starting point for meaningful results-oriented negotiations leading to a settlement” as well as reports that provide “integrated, evidence-based and data-driven analysis, strategic assessments and frank advice to the Security Council, to describe the mission’s impact and overall mission performance”. It is unclear what these might mean, but it undoubtedly adds further uncertainty for Cypriots, in case UNFICYP either withdraws, further reduces its personnel numbers, or changes its mandate from a peacekeeping force to a mission for observation purposes only.

In any case, these will be Guterres’ last reports to the Security Council, as he is completing two terms and will be stepping down at the end of 2026. The time he has to devote to the Cyprus issue is limited, given the weight of international crises and conflicts at a time of international turmoil and challenges to the role of the UN. At the same time, the Secretary-General has recently warned that the international organization is at risk of financial collapse by mid-year if major financial contributors, such as the US, do not pay their dues. In November, he was forced to make drastic cuts that affected the deployment of peacekeeping missions, including in Cyprus, which is currently limited to a few hundred personnel, while it is responsible for patrolling the buffer zone and the 180 km ceasefire line.

The postponement of the informal “5+1” meetings under these circumstances is a very negative development and a bad sign.

Reservations

Guterres had long had reservations about the consecutive Cypriot leaders’ unanimous commitment to resolving the frozen conflict. He has recorded his reservations in his regular reports since 2017. That year, he had just assumed the duties of secretary-general and personally witnessed the collapse of negotiations in Crans-Montana, when the two leaders, Nicos Anastasiades and Mustafa Akıncı, were on the verge of a strategic agreement. However, the parties left without reaching an agreement. The talks stalled after the failure, and in 2020, following the election of Ersin Tatar, the Turkish Cypriot leadership aligned its position with Turkey and abandoned the federal basis for a solution. he differences between the sides became irreconcilable.

Under the weight of the deteriorating situation on the island and at the request of both Cypriot leaders, Guterres decided in 2024 to re-engage through informal “5+1” meetings. He convened two such meetings in 2025, in March in Geneva and in July in New York, and he intended to convene a third, provided that the Cypriot leaders would first show some signs of progress, at least in terms of confidence-building measures such as opening crossing points.

The negative developments in January dashed the brief hopes raised in December when the two current leaders of Cyprus, Christodoulides and Erhürman, agreed that “the real aim is the solution of the Cyprus problem with political equality as described in the UN Security Council Resolutions”. They also agreed at the time that “confidence building measures are important for creating a conducive environment but are not a substitute to achieving a solution to the Cyprus problem.”

This positive development was welcomed by the Secretary-General, who wrote in his report to the Security Council on January 5 that “there is a new opportunity to move forward on the Cyprus issue.” He even noted that “for the first time in more than five years, discussions on core political issues took place.” Encouraged by the new developments, Guterres called for careful steps and “encouraged the two leaders to conclude an agreement on opening new crossing points without delay, given that crossings can have a tangible positive impact on the daily lives of people and increase contact between the people, which ultimately strengthens mutual understanding, trade and economic interdependency.”

Four crossing points – but which four?

The UN focused on confidence-building measures, placing emphasis on opening new crossing points at the previous two informal “5+1” meetings. Ersin Tatar was the leader of the Turkish Cypriot community at the time. Last March, Guterres secured an agreement between the two leaders to open not just one, but four new crossing points. However, by July, when he convened the second informal meeting, Christodoulides and Tatar had failed to agree on which four crossing points would be opened. The meeting ended with weak announcements and the process was put on hold pending positive news from the leaders.

In October, a new Turkish Cypriot leader was elected, and in December, the first encouraging joint statement by Christodoulides and Erhürman was issued. The UN Special Envoy, Maria Angela Holguin, urged them “to strengthen this early momentum and build genuine trust” in order to convene a third informal “5+1” meeting. “If I had to single out one measure, it would be new crossings, they send the strongest positive signal of political commitment and have the most immediate impact on people’s lives,” she said.

And now…

In its recent resolution, the Security Council fully aligned itself with the Secretary-General’s recommendations on the need of a full range of confidence building measures and encouraged “further efforts by the leaders to deliver on the agreed trust-building initiatives, especially on the issue of opening of new crossing points.”

It also linked crossing points to a number of other factors that would contribute to the settlement of the Cyprus problem, such as “the promotion of intercommunal contacts, intra-Cyprus trade, reconciliation, and the active participation of civil society.” In the same context, the Security Council noted that “the socio-economic gap between the two Cypriot communities has widened further” (to the detriment of Turkish Cypriots). This “may intensify alienation and undermine the prospects for a solution,” it added.

All efforts have been in vain so far!

In a written statement on January 28, Holguin said that (the two leaders) “will now continue efforts to reach agreements on the various trust-building initiatives that are on the table as well as towards the start of substantive negotiations.”

The two leaders agreed to meet again later in February. Holguin hopes to see substantive and real progress in the short term, but she stressed that before returning to the island, she would want to see concrete developments on the ground in terms of confidence-building measures.

Negotiations

The two leaders disagree fundamentally on which of the previous body of work to use to resume substantive negotiations and which methodology they will follow thereafter, even though both cited in their written memoranda to the Secretary-General as a chronological starting point “the convergences achieved up to Crans-Montana.”

During the January 28 meeting Christodoulides presented a proposal asking the UN to put in writing whatever the parties would agree on based on the convergences up to Crans Montana. He stated verbatim the aim of this as, “to keep in writing what the two communities agree on for the internal aspect (of the Cyprus issue) and what the five parties (i.e., the two communities and the three guarantor powers) agree on for the external aspect.” “On the basis of this document of convergences, formal negotiations should begin,” he said. There is no written text other than his statement, which was only in Greek.

Erhürman submitted his own proposal in writing insisting that both sides have to reconfirm before resuming negotiations, “the commitment to the principle of political equality, including rotating presidency and effective participation (including at least one favourable vote (from each community) in taking a positive decision.” He also proposed that “the convergences achieved up to Crans Montana will not be renegotiated.”

In terms of methodology, Christodoulides advocates an immediate resumption of open-ended negotiations based on the proposal he presented.

Erhürman demands that “the new process will be result-oriented and time-framed” for reaching an agreement. He adds that in the event of failure caused by the Greek Cypriot side, “Turkish Cypriots will not be condemned to their current status in the eventuality that the process does not reach a successful conclusion, despite their best efforts.”

The proposals both by Christodoulides and Erhürman are characterised by a lack of clarity that is neither constructive nor sufficient for citizens to understand what has been agreed upon up to the Crans Montana talks. Christodoulides’ proposal refers to an extensive renegotiation of the body of work leading up to the final stage of Crans Montana, while Erhürman’s proposal focuses explicitly on only one of the six key remaining points in Crans-Montana, namely political equality, which is a priority for the Turkish Cypriot community.

Christodoulides and Erhürman refer to the convergences of Crans Montana, but they omit a very important document, which was presented to them at the time by the Secretary-General aimed at guiding them to reach a strategic agreement on all six outstanding negotiating chapters.

However, in his report to the Security Council in September 2017, the Secretary-General had described in more detail and with greater clarity how close the parties had come to reaching an agreement in Crans-Montana (paragraphs 18-26). He also referred to the six points that remain at the core of the negotiations: guarantees and troops (security), territory, property (assets), equal treatment (of Turkish citizens), and power-sharing. In paragraph 27 he summarised these verbatim:

“By the time the Conference closed, the sides had essentially solved the key issue of effective participation. While some differences remained on the equivalent treatment of Turkish nationals with regard to the issue of free movement of persons, they were a question of certain details rather than principles. An incipient agreement was also emerging on territorial adjustment. With regard to property, the sides had agreed in principle on two separate property regimes, while some details again remained. Finally, the participants had significantly advanced in developing a security concept, on the assumption that agreement was reached on all domestic aspects of the settlement to the satisfaction of both communities.”

The Secretary-General, having assessed the positions of all parties in Crans-Montana, concluded “that there was a broad understanding of the parameters of the potential strategic agreement”, but in the end, the parties lacked the determination and confidence to reach it.

This lack of determination and confidence continues to this day.

Based on the positions of the two sides, the UN considers it premature to convene formal, full-scale negotiations. The Secretary-General has repeatedly stated that he does not want endless discussions, but rather “result-oriented” negotiations and is now calling for confidence-building measures with tangible results to be taken first, singling out the opening of crossing points, on which the Security Council also agrees.

That is why the Secretary-General argues that confidence-building measures are absolutely necessary to create realistic conditions with real chances of success.

What is the issue with the crossing points?

Christodoulides calls for an official conference to be agreed upon first, and for full-scale negotiations to resume in order to announce an agreement to open four new crossing points. He proposes the following four: Kokkina (Erenköy), Louroujina (Akıncılar), Mia Milia (Haspolat), Athienou-Aglantzia (Kiracıköy – Eğlence)

Erhürman supports the opening of all crossing points as part of a comprehensive package of confidence-building measures to create a “climate conducive to solution” of the Cyprus issue. He proposes: Mia Milia/Haspolat, Louroujina/Akıncılar, Athienou/Kiracıköy, and Aglantzia/Eğlence.

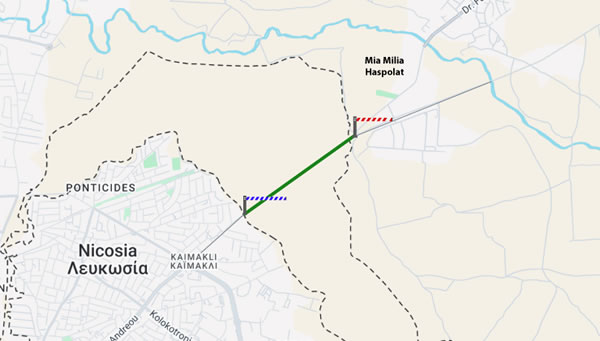

Mia Milia/Haspolat

The most important crossing point that has already been on the table for discussion since 2023 is Mia Milia/Haspolat, in the eastern suburbs of Nicosia. This is a roadblock on an existing avenue that can easily be demolished and provide access to citizens. The area that is within the buffer zone is short and offers plenty of space for the necessary infrastructure, including multiple lanes for vehicles. If opened, Mia Milia/Haspolat is likely to increase crossings more than ever before, as it would serve the wider Nicosia area, which is the most populous area on the island.

For 22 years, the divided capital has been left with just one crossing point for vehicles; , the Ayios Dometios/Kermia crossing point in the western suburbs. According to statistics, more than 70% of all crossings occur at this crossing point, which has the highest congestion and longest lines compared to the other eight crossing points operating along the Green Line. This means hours of waiting even for daily, routinethings, like going to work or school across the divide. In combination with the improvement of the existing crossing point at Ayios Dometios/Kermia, Mia Milia/Haspolat would alleviate the congestion, and at the same time, facilitate bicommunal trade.

In the early stages, the discussion about Mia Milia/Haspolat focused on allowing only taxis, buses and commercial vehicles in an effort to support bi-communal trade. This has now changed and, if opened, Mia Milia/Haspolat would serve everyone, according to a proposal by the Greek Cypriot side, the Greek Cypriot negotiator Menelaos Menelaou says.

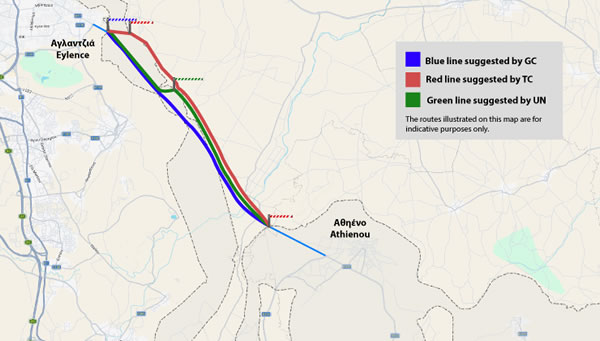

Athienou and Louroujina

The Greek Cypriot town of Athienou and the Turkish Cypriot village of Louroujina are located in the heart of the Mesaoria plain, but are geographically isolated due to the ceasefire line which creates a deep narrow strip to the south to reach Louroujina. The opening of these two crossing points would provide many opportunities for local development and alternative routes for vehicles, facilitating the connection of Athienou and Louroujina with large cities, as well as communication and exchanges between the two communities.

Athienou is currently disconnected from Nicosia. Connection with the capital city could theoretically be achieved by using the old road that existed before 1974. A large part of this road is located within the buffer zone, but it passes through a narrow strip of land near the village of Piroi, which is a Turkish military zone, before reaching the University of Cyprus in Aglantzia.

According to local media reports, the Greek Cypriot side had initially requested to open this route through the buffer zone implying that no checkpoints would be necessary. During the summer, the Turkish Cypriot side proposed a route outside the buffer zone, above the Turkish ceasefire line, with two crossing points at Athienou and Aglantzia (University of Cyprus). The Greek Cypriot side rejected the route, citing time-consuming and costly procedures for acquisitions and insisted to use the pre-74 road.

Christodoulides stated on January 28, that he would accept the UN proposal for a route variation. This proposal involves a modification of the route proposed by the Turkish Cypriot side so that it passes from Athienou to the north, but enters the buffer zone near Geri before ending up in Aglantzia. This would mean that two crossing points would be set up, in Athienou and Geri. The total distance that needs to be covered from Athienou to Aglantzia in each proposal does not differ significantly.

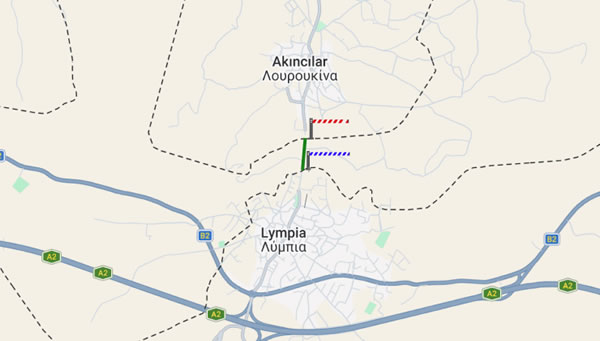

No explicit disagreement has been recorded regarding the crossing point that will connect Louroujina with the town of Lympia. The distance between the Greek Cypriot and the Turkish Cypriot settlements is just a few hundred meters.

Kokkina/Erenköy

Christodoulides’ proposal for Kokkina/Erenköy concerns a crossing point near the coast where there is a small Turkish enclave, which is a Turkish military camp, completely isolated since 1964, with just sea access. Kokkina is surrounded by hills with military positions of the National Guard. The route proposed by the Greek Cypriot side along the coast would significantly shorten the distance between the village of Pyrgos and the villages on the north coast towards the town of Polis – Chrysochou and the district of Paphos. Objectively, the area is heavily militarised.

Christodoulides insists, in particular, on this crossing point and argues that it has long been a Greek Cypriot demand and cannot be abandoned. This view is repeatedly disseminated in the Greek Cypriot media, accompanied by the argument that the Turkish Cypriot proposals are acceptable (Mia Milia, Louroujina), the Greek Cypriot side is showing flexibility on Athienou, while the Turkish Cypriot side is not reciprocating and remains adamant on Kokkina. Erhürman has claimed that while the United Nations made a proposal for Athienou, it made no reference to Kokkina.

The discussion on the “four crossing points package” has so far been hampered by the deadlock over the Kokkina/Erenköy issue, which has become a stumbling block.

However, alternative proposals have been put forward in the meantime. The two heads of the local authorities in Nicosia, Charalambos Prountzos and Mehmet Harmancı, have proposed opening another pedestrian crossing within the walls of Nicosia, similar to the one at Ledra Street/Lokmacı which also experiences significant congestion. This is a connection via Lidinis Street that links the new Nicosia City Hall in the south with the Turkish Cypriot “Pantopolion” (Bedesten/City Market) in the north. Christodoulides mentioned this briefly, but there has been no follow-up. Harmancı also proposed another crossing for pedestrians and vehicles further east of Mia Milia/Haspolat in the Kaimakli suburb of Nicosia.

The works in Ayios Dometios/Kermia to increase the capacity of the crossing point, are currently the only positive development, but even those only came along after years of delay. On its own, the Ayios Dometios/Kermia crossing point is not sufficient to change the current situation.

Crossing points: not a strategy to help resolve the problem but a vehicle to undermine resolution

The Security Council stresses the need for progress towards the resumption of formal negotiations “on the basis of a bi-zonal, bicommunal federation with political equality,” supports the opening of crossing points, and calls on the leaders to cooperate with the Secretary-General “with a sense of urgency.” It underlines that “the responsibility for finding a solution lies first and foremost with the Cypriots themselves.”

The failure to agree on new crossing points shows that confidence-building is not an integral part of the leaders’ strategy to help resolve the problem. On the contrary, it is being used as a vehicle to suspend or undermine efforts to find a solution. Discussions on a package deal for four crossing points are rife with expediency and tactical maneuvering. Each particular point is turned into a matter of prestige, a give-and-take with a zero-sum outcome. The needs of citizens, the importance of interaction, and the daily hardships people face come second. The fact that each leader is proposing different crossing points shows that they are guided by domestic public opinion, rather than a genuine will to solve the Cyprus problem. Promoting bi-communal cooperation and communication, as emphasized by the United Nations, does not appear to be a priority for them.

Paradox

Cypriots feel the paradox of the unresolved Cyprus issue more than ever before. As citizens, both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots belong to the European Union, but the two communities live separately. The prospects for reunification are more distant than ever before. Cypriot leaders are unable to find a way to restart the process, and the climate they continuously create is confrontational and counterproductive.

Thousands cross daily through nine crossing points along the Green Line

Despite the negative climate, the number of citizens crossing the divide is increasing steadily every year. From 120,000 at the beginning in 2004, (Greek Cypriots 50,000, Turkish Cypriots 70,000), it reached 1,200,000 (Greek Cypriots 480,000, Turkish Cypriots 460,000) in 2019. After the covid pandemic, crossings skyrocketed. Based on the latest data provided by the EU One Stop Shop and the Cyprus Police, in 2024 crossings reached a total of almost 6 million (Greek Cypriots 2,528,106, Turkish Cypriots 3,456,622) and in 2025 to 6.5 million (Greek Cypriots 2,787,622, Turkish Cypriots 3,728,577). In addition to Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot crossings, there has also been an increase in crossings by non-Cypriots, other Europeans, and third-country nationals, which reached 1.8 million in 2024 and exceeded 2 million in 2025. Accordingly, the number of vehicles passing through the crossing points is also increasing, which, according to the most recent count for 2025, now exceeds 5,000,000 per year.

As a proportion of their population, Turkish Cypriots cross more frequently over time than Greek Cypriots. The recent steady increase in crossings by Turkish Cypriots is related, among other things, to consumer goods that are now cheaper in the Republic of Cyprus due to the high cost of living in the northern part of the island caused by the fall in the value of the Turkish lira. Significant expenditure is also observed by both communities across the crossing. Based on credit card usage records, in 2024 Greek Cypriots spent €45,543,267 and Turkish Cypriots €49,076,473. Cash transactions are estimated to be double these figures.

A policy of contradictions

There are nine crossing points along the Green Line. The first four crossing points had opened in 2003 to allow Cypriots to meet for the first time after almost three decades of complete separation. Two crossing points were located in Nicosia, at Ledra Palace and Ayios Dometios/Kermia, while the other two were in Pergamos and Strovilia, where the British bases in Dhekelia directly border the dividing line. The first crossing points were opened by a unilateral decision of the Turkish Cypriot leadership and with the approval of Turkey.

On May 1, 2004, the Green Line Regulation (GLR) came into force and, since then, crossing points have been operating on the basis of European law. The authorities of the Republic of Cyprus “carry out checks on all persons crossing the line” as well as on “vehicles and objects in their possession.” Crossings are only permitted at designated crossing points for reasons of security, public order, and combating illegal immigration: “every person shall be subject to at least one check to verify their identity.”

By 2010, the leaders of the two communities had agreed to open three more crossing points. Specifically, in 2006, the Astromeritis-Zodia/Bostancı roadblock was opened. This crossing point was opened a few weeks after the approval of EU regulation for the provision of financial assistance to the Turkish Cypriot community. Subsequently, Ledra Street/Lokmacı was opened to pedestrians in 2008 and the Pyrgos/Limnitis crossing point in 2010. Sixteen years have passed since then, and crossings have increased from 460,000 (2010) to 6.5 million. Eight years had to pass after Pyrgos/Limnitis, to open two more crossing points: Deryneia-Ammochostos and Lefka-Apliki/Aplıç, in November 2018.

In rhetoric, the authorities of the Republic of Cyprus do not prevent citizens from crossing the border. In a recent statement, President Christodoulides reminded journalists, who asked him about crossing points that “in 2003, it was the occupying regime that decided to partially lift the restrictions.” He explained that “the authorities of the Republic of Cyprus never prevented crossing into the occupied areas, but Turkey and the occupying regime did.”

In principle the Turkish Cypriot leadership also favors the opening of crossing points. Those leaders who support a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation with political equality are in favour of and supportive of such initiatives for bi-communal cooperation. Those, who oppose a federal solution view interaction with the Greek Cypriot community negatively.

Several political parties among the Greek Cypriots reject the crossing points and criticize those, who use them. These positions echo parties that also disagree with a bizonal bicommunal federation. Most of these parties supported the election of Nicos Christodoulides, currently participate in his government, and support his handling of the Cyprus issue.

The approach of the respective leaders of the two communities to the opening of crossing points has been inconsistent. The first crossing points were opened by a unilateral decision of the Turkish Cypriot leadership in April and May 2003. Since 2004, the Greek Cypriot leadership has argued that they should not be a substitute for a comprehensive settlement. But 22 years have passed since then, with long periods of stagnation and no prospect of a solution. According to the Green Line Regulation, the opening of each crossing point creates obligations for the Republic of Cyprus as well as the Turkish Cypriot administration, including infrastructure and checks. These necessitate prior consultation between the two sides. Opening of crossing points also requires the withdrawal of military forces.

Looking at the timeline for the opening of crossing points, it’s clear that new ones were opened to encourage a climate of meaningful negotiations for a solution only in 2008 and 2010 . At that time, Dimitris Christofias and Mehmet Ali Talat were in leadership positions. In all other cases, leaders opened crossing points rather to defuse international reaction and internal disappointment after a resounding failure in the efforts to reach a settlement.

This is what actually happened between 2004 and 2006, after the referenda on the UN Peace Plan (Annan Plan) failed. The same situation was repeated in 2018, after the failure of the Crans Montana talks. In 2015-17, when Anastasiades and Akıncı held intensive peace talks, a positive shift in public opinion towards confidence-building was seen. The two leaders were absorbed in intensive negotiations and did not open any crossing points. The trust they built in various other areas was subsequently lost.

TABLE: Timeline of Crossing Points

| Crossing Points (9 opened) | Year |

|

Ledra Palace, Ayios Dometios/Kermia & Pyla/Pergamos and Strovilia – both UK British Bases |

2003 |

|

Astromeritis-Zodia/Bostanci |

2006 |

| Ledra Street | 2008 |

| Limnitis/Pyrgos | 2010 |

| Derynia & Lefka | 2018 |

|

Widening Ayios Dometios Plan to open 4 new checkpoints – no agreement |

2025-2026 |

Source: European Commission – One Stop Shop

This comparative analysis confirms the key observation made by the UN that building trust through initiatives such as opening crossing points, intra-Cyprus trade, and bi-communal cooperation should not be occasional but rather inextricably linked to efforts to resolve the long-standing conflict.

“Trust is built slowly and can be eroded quickly. What I have observed is that the obstacles are not only political, but also psychological. Many decades without a comprehensive settlement have understandably created fatigue, caution and, in some cases, scepticism about whether progress is possible. Narratives of the past still weigh heavily on the present.”

Maria Angela Holguin

The European dimension

The European Union is aligned with the UN’s strategic approach to confidence-building through its own initiatives, having repeatedly declared its support for UN-led efforts to resolve the Cyprus issue. Last May, President Ursula von der Leyen of the European Commission appointed former Commissioner Johannes Hahn as her envoy on Cyprus to support “all stages of the process” for resolving the Cyprus issue.

During his visit to Cyprus in December, Hahn said in an interview that “we share with the UN the goal of building trust between the two communities and finding a sustainable solution for Cyprus.” EU initiatives include the creation of bi-communal projects such as a photovoltaic park in the buffer zone. The EU also funds a number of bi-communal cooperation projects, including infrastructure at crossing points, the promotion of intra-Cyprus trade, the work of the Committee on Missing Persons, and the restoration of cultural heritage monuments (churches, mosques, Venetian walls, etc).

The political debate on crossing points is often accompanied by a vast ignorance of the legal reality that has been created since Cyprus joined the EU.

The legal status of the crossing points for persons and goods is determined by the Council of the EU through the GLR and aims to facilitate relations between the two communities pending the resolution of the Cyprus problem. Cyprus entered the EU as a divided island, while the Green Line is explicitly defined as being “not a border.”

The GLR is based on Protocol 10 of the Treaty of Accession of Cyprus to the EU, which stipulates that “the application of the acquis is suspended in the areas of the Republic of Cyprus in which the Government of the Republic of Cyprus does not exercise effective control” (Article 1).

The Protocol “does not preclude the adoption of measures to promote the economic development of those areas” (Article 3). Furthermore, the suspension of the application of European law does not affect the individual rights of Turkish Cypriots as EU citizens. They are citizens of an EU country, regardless of whether they live in a part of Cyprus that is not under the control of the Government of Cyprus.