Focusing on the big picture, the geopolitical benefits of an electric interconnection between Israel‑Cyprus‑Greece via the GSI cable are relatively obvious. When you consider the major natural gas reserves, the strategic maritime routes, and the possibility of undersea energy cables, the Eastern Mediterranean’s significance becomes especially clear.

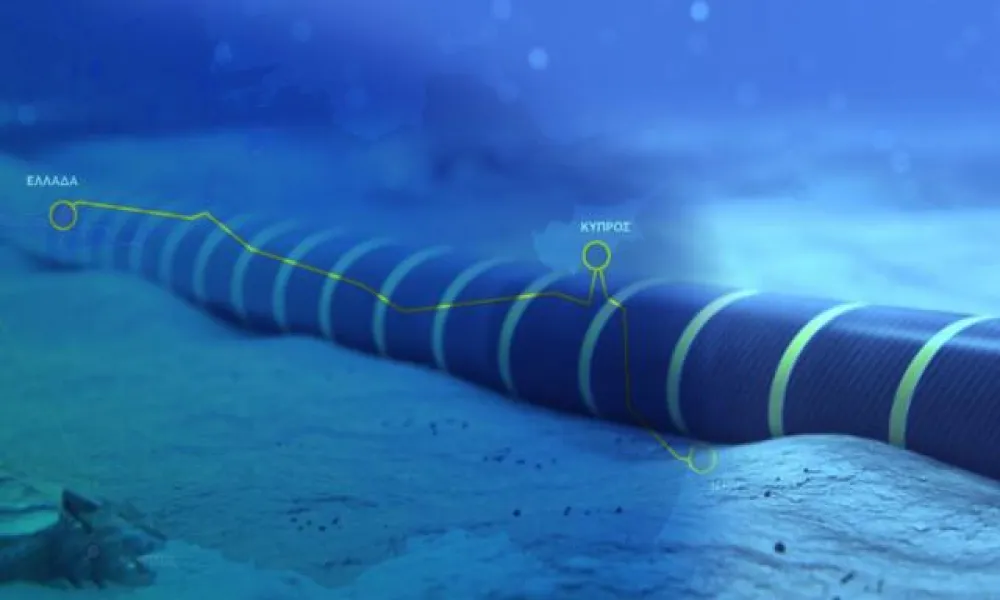

Such a cable could connect Cyprus and Israel with Greece (and by extension the rest of Europe), offering a reliable, two‑way submarine link. With further upgrade and extension, it could also include Turkey via Cyprus, and the Middle East through Israel, creating a unified, dependable energy transport system at better cost.

Unfortunately, that plan isn’t currently in place, and the prospect of realising it seems to be slipping further away. The project has become murky, especially due to a lack of transparency — particularly on the financial front. Perhaps the biggest problem is the absence of politicians with rational analysis and vision. If they had existed, this interconnection, just as with others in the EU, would have been implemented years ago. Even now, were the interconnection to proceed, some emerging technologies now in experimental stages may overtake it and render the project unviable.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, a key barrier to such developments is establishing clear maritime boundaries (exclusive economic zones, or EEZs). The lack of resolution here causes ongoing irregularities, yet it receives far less attention than it deserves. Only Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel—and to some extent Greece with Egypt—have managed this successfully. All other countries – Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Libya, etc. – remain far apart on agreements. Turkey particularly claims nearly half the Eastern Mediterranean but hasn’t resolved any EEZ agreement with other states.

Turkey has some 1,600 kilometres of coastline in the Eastern Mediterranean, with over 10 million Turkish citizens living along those shores. Under the Law of the Sea, it may be owed a substantial EEZ, but it pursues those claims often by force: interfering with Cyprus’s drilling efforts, opposing Greek cable‑laying, and pursuing contentious agreements like the Turkish‑Libyan memorandum. These actions provoke conflict with Greece and Egypt, among others.

Greece and Cyprus also to blame

Why don’t we see proper EEZ demarcation? Greece and, to a lesser degree, Cyprus share responsibility. The Mitsotakis government has shown realism in negotiating EEZs with Italy and Egypt, conceding that certain small islands north of Corfu and west of Zakynthos, and parts of the Dodecanese, cannot hold equal weight in those agreements.

Similarly, Kastellorizo remains isolated and unable to influence EEZ determinations, so much so that some maintain Greece’s EEZ overlaps with both Cyprus’s and Egypt’s.

Given the intense disputes over maritime boundaries among Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus, shouldn’t there at least be basic agreements about submarine cables and pipelines — whose routes are harmless — to move forward despite political gridlock?

Let’s be frank: Turkey’s demands are often extreme; but that does not mean it has no rights in the Eastern Mediterranean. Equally, Greece, Cyprus and Israel should not pre‑exclude Turkey whenever new energy projects are planned. This has happened again and again: with the EastMed gas pipeline and the proposed GSI electricity cable. EastMed was abandoned because the gas reserves were too small to justify a 1,200‑mile pipeline. GSI faltered because Greece avoided formal engagement, allowing Turkey to respond aggressively, including with naval force to block surveying vessels between Karpathos and Cyprus.

Also underappreciated is Turkey’s substantial influence over major energy players. So much so that potential new drilling in Cyprus (and surplus gas in Israel’s Leviathan field) could be rapidly sold in Turkey at acceptable prices. Yet Cyprus chose to sell its gas to Egypt essentially at cost.

In short, if we had leaders of substance rather than opportunistic politicians, given the reserves Israel and Cyprus hold the pipeline or cable would be planned to traverse maybe 100 miles across Turkey rather than stretching 1,200 miles to Italy. For that to happen, though, necessary preconditions include resolution of the Cyprus problem and Greek‑Turkish issues, to open the door to economic cooperation and peaceful coexistence.

What does this lack of agreement lead to? Instead of resolving outstanding disputes, we have entered a strategic competition. Greece and Cyprus build alliances, military bases, war airports, infrastructure meant partly to control sea routes, demarcate maritime zones for drilling, and lay telephone and power cables.

The price of disunity

Where are we now? Rather than building energy, trade, communications and other bridges that include everyone, we are trapped in a rivalry whose end is unclear — possibly even war.

During the administrations of Anastasiades and Christodoulides, Cyprus appears to have been led astray by Netanyahu’s policies, with Cyprus, Greece and others dragging along without significant results from various trilaterals.

Some take this further, arguing that following the withdrawal of US and Russian influence, and the retreat of Iran and Assad’s Syria, a power vacuum opened—one Israel might fill with Greece and Cyprus, excluding Turkey, bringing it “to order” as it did Iran. It’s an opportunistic view born of naive nationalism, unlikely to lead anywhere. In fact, Turkey’s influence in the region has risen sharply over the past two years; confrontation with it yields little except mutual damage.

At the end of the day, Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and Turkey stand to gain far more if they accept political coordination and economic cooperation. If instead they persist in confrontation—a path which could lead to uncontrolled outcomes—everyone will lose.

The international stage today unfortunately does not favour calm, rational approaches to solving problems.